Two years have slipped by since Abdul Razak Dawood, the then Adviser on Commerce to the Prime Minister, first breathed life into the concept of a petrochemical policy. Now, Pakistan teeters on the precipice of finally sculpting its maiden petrochemical policy. Media murmurs this week hint that the Government of Pakistan is meticulously applying the final brushstrokes to the policy, and the industry is positively buzzing with anticipation.

However, let’s address the elephant in the room. Many of the industry’s most seasoned stakeholders are left scratching their heads over the policy due to the protracted delay since its initial announcement. Let’s take a moment to jog our memory and revisit what we know thus far.

According to media whispers, the policy aims to lure investment into the midstream industry to kickstart indigenous manufacturing of petrochemicals. The Engineering Development Board (EDB) is currently engaged in consultations with public and private sector stakeholders to put the finishing touches on the Petrochemical Policy of Pakistan (2023). The goal? To ignite indigenous manufacturing of petrochemicals such as polypropylene, polyethylene, LAB, etc., and ensure sustainable development through local availability of plastic resins for the downstream engineering industry.

A draft policy was reportedly handed over to the Ministry of Industries & Production in July 2023 and is currently under scrutiny from relevant Ministries/Divisions. It will subsequently be presented before the Economic Coordination Committee of the Cabinet for consideration.

The proposed policy is anticipated to yield a plethora of benefits. It is expected to ensure the availability of essential raw materials for a wide array of downstream sectors. These include, but are not limited to, textiles, construction, automobiles, pharmaceuticals, fertilisers, and synthetic rubber.

While all the specifics related to the policy remain cloaked in secrecy, there’s no denying that anticipation within the industry is reaching fever pitch.

“The Government deserves a round of applause for prioritising the development of a long-term roadmap for the petrochemical sector,” declares Jahangir Piracha, CEO of Engro Polymer & Chemicals. He continues, “This could be a catalyst for industrialisation in Pakistan.”

Piracha underscores the need for a petrochemical policy that encompasses both existing and new petrochemical assets. He states, “It’s crucial to attract substantial investments into these projects which are capital intensive and have long gestation periods.” He also tips his hat to Pakistan’s existing petrochemical players, saying, “They invested during challenging times and it’s their success that will pave the way for large-scale petrochemical investments.”

Echoing similar sentiments, Asif Jooma, CEO of Lucky Core Industries asserts, “Petrochemicals form the backbone for multiple industries in Pakistan and have been instrumental in supporting various downstream industries and services.” He adds, “They are one of Pakistan’s largest imports and investments in this sector are pivotal for the country’s economic growth.”

Now, while this may be the sector’s first brush with a dedicated petrochemical policy, it certainly isn’t Pakistan’s maiden voyage into industrial policy. In fact, Pakistan’s tryst with industrial policy has been somewhat chequered. Profit reached out to the EDB to understand their rationale behind selecting this particular sector but was met with silence.

So, will this time be any different? But first things first – what exactly are petrochemicals and why does it seem like they’re being singled out by the Government as a sector in need of a dedicated policy?

What are petrochemicals?

The midstream segment of the petrochemical industry encompasses monomers and polymers. These are derived from naphtha cracking and utilised by the downstream segment to create a myriad of plastic products. These include, but are not limited to, sheets, films, tubes, profiles, containers, filaments, ropes, and more. These products find their application in a wide array of industries such as packaging, construction, automotive, industrial products, wind turbines, solar panels, electrical & electronics, artificial leather, home appliances, bottles & jars, furniture, kitchen wares, household toys, disposable utensils and packaging.

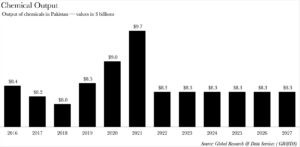

The major petrochemical products currently manufactured in Pakistan include poly-vinyl-chloride (PVC), polystyrene (PS), purified terephthalic acid (PTA), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), phthalic anhydride (PA), and linear alkyl benzene sulfonic acid. However, it’s worth noting that Pakistan’s chemical sector appears to have hit a roadblock. The output seems to have stagnated at $8.3 billion. This is a step back from its 2021 peak of $9.7 billion. Moreover, if all other factors remain constant (ceteris paribus), this trend is expected to continue until 2027.

| Output by Type of Chemical | |||

| 2016 | 2022 | 2027 | |

| Basic chemicals | $2,177 million | $2,141 million | $2,141 million |

| Fertilisers and nitrogen compounds | $2,658 million | $2,613 million | $2,613 million |

| Plastics and synthetic rubber in primary forms | $696 million | $685 million | $685 million |

| Pesticides and other agrochemical products | $352 million | $346 million | $346 million |

| Paints, varnishes, printing ink and mastics | $671 million | $659 million | $659 million |

| Soap, cleaning and cosmetic preparations | $1,594 million | $1,567 million | $1,567 million |

| Other chemical products | $236 million | $232 million | $232 million |

| Man-made fibres | $62 million | $61 million | $61 million |

| Source: Global Research & Data Services ( GR&DS | |||

So, could investments in the sector bring about any meaningful change?

Piracha posits that a $1 increase in petrochemical output could potentially amplify the gross domestic product by approximately $4, courtesy of a high GDP multiplier effect. “Pakistan’s petrochemical sector is underdeveloped; we are one of the few large economies without a cracker,” Piracha rues. He sees a silver lining in the mid-stream petrochemical sectors, which he believes offer an opportunity to invest $3 billion. “The strong local demand for six products – polypropylene, PTA, PET, PVC, Methanol and linear alkyl benzene – justifies the setup of world-scale plants in Pakistan,” Piracha adds.

This then posits the question: why do you need an industrial policy with tariff production if there’s already domestic demand for the sector to capitalise on?

Why the need for consistency?

Two pivotal factors are at play here: the imminent Saudi refinery and the potential for stability to catalyse the sector’s growth.

The Petroleum Refining Policy, formally known as the Pakistan Oil Refining Policy for New/Greenfield Refineries 2023, was unveiled earlier this summer. This policy has been tailored specifically for a single project – a greenfield deep conversion integrated refinery and petrochemical complex with a crude oil processing capacity of 300,000 barrels per day (bpd). This project is being established in collaboration with Saudi Arabia. The policy does not permit any future refinery projects that utilise a different oil refining process or technology other than deep conversion, or have a capacity less than 300,000-bpd. Moreover, it stipulates that it must be an integrated refinery and petrochemical complex, regardless of feasibility. Refinery projects with a capacity of less than 300,000-bpd will be considered under a separate package offering lesser incentives and concessions.

Rumours are also circulating that the installed capacity of the Saudi Refinery may be increased to 400,000 bpd.

While the refinery sector may not be entirely pleased with the policy, it could prove to be a boon for the petrochemical sector. Firstly, at 300,000 bpd, the Saudi refinery would become the largest in Pakistan, boasting a cumulative capacity equivalent to that of PARCO and Cnergyico’s combined – currently the two largest refineries in the country. This would not only ensure a steady supply of feedstock for the petrochemical sector from the refinery but also stimulate ancillary industries into action and pave the way for economies of scale for whichever Pakistani company manages to achieve them.

Furthermore, the 300,000 bpd limit in the refining policy suggests that the forthcoming petrochemical policy may also set similar production thresholds for players wishing to capitalise on the sector. While this could further limit the sector to even fewer players than currently exist, it also ensures that those who do operate will be running world-scale plants. This brings them closer to achieving economies of scale and potentially contributing to the country’s exports.

The existence of such a policy would also provide much-needed consistency to the sector. Petrochemical plants typically take around four to five years to become operational. Therefore, any large-scale investment would require safeguards for at least that period. One common sentiment echoed across our interactions with various sector stakeholders was their hope that such a policy would shield the sector from erratic decisions like the super tax.

However, this is where our optimism concludes. This is not Pakistan’s first industrial policy, nor is it likely to be our last. Based on historical precedents, we have an established track record of either botching policies or setting up policies destined for failure from their inception. Let’s now examine all the ways this policy could potentially go awry.

How to tentatively botch the policy altogether

First and foremost, when a sector is shielded by tariffs, it invariably exerts pressure on the downstream sector. This could be either inadvertent or deliberate. The downstream sector then protests that their production costs have escalated due to the additional protection granted to the upstream sector (or midstream in our case), leading to a tug-of-war. The government typically finds itself in the middle of this struggle, necessitating the intervention of the National Tariff Commission to resolve the issue.

This is precisely what transpired with polyester, PTA, and polymers.

“The domestic market needs to be naturally large enough to attract investors. If it isn’t, no one will invest regardless of the artificial gains you provide,” states Asif Saad, former CEO of Lotte Chemical.

“Shielding one or two products in the value chain engenders imbalances and is not favourable for the growth of the entire sector. The examples of synthetic polyester and pvc show that they are unable to grow to any significant scale despite the high level of tariff provided historically,” Saad adds. .

“China and India invested in domestic capacity building to achieve economies of scale and then gain competitive advantages in global markets. The government needs to invest in large-scale infrastructure. It needs to enhance ports, storage tanks, shipping etc., so that the petrochemical producer is provided with a plug-and-play model. Currently, all of this is undertaken by the companies in the sector themselves,” Saad continues.

“Petrochemical is also a broad term. You can’t have one policy for the entire sector. You need to narrow the scope to provide investors with greater clarity. Paraxylene, for example, has its own value chain that requires the refiner to allocate additional molecules. Every product in the sector has its own value chain,” Saad criticises.

While the sector may be elated with the incoming policy, there’s also perhaps a hint of bitterness across them. This will be the country’s first policy of its kind, and they will now be competing in a world dominated by large incumbents, with China and India being just the most recent additions. Some might even argue that the opportunity to develop the sector to compete with regional and global peers perhaps sailed thirty years ago.

However, now that we have a policy on the horizon, we can only hope that this is not a repeat of our automotive experiments. “To fully leverage the benefits of scale and integration, it is highly beneficial to evolve a policy that addresses the current and future needs of an integrated refinery and petrochemical complex,” emphasises Jooma.

Global Corrugated Packaging Market expected to reach approximately USD 317 Billion in 2023, growing at a CAGR of slightly above 3.5% between 2017 and 2023”

Global Corrugated Packaging Market expected to reach approximately USD 317 Billion in 2023, growing at a CAGR of slightly above 3.5% between 2017 and 2023”

The appealon zero plastic, especially for consumer goods packaging is accelerating although slowly, according to a report produced by the UK-based Green Alliance Circular Economy Task Force (CETF) comprising of members including Kingfisher, Viridor, Walgreens Boots Alliance, SUEZ recycling and recovery UK, and Veolia.

The appealon zero plastic, especially for consumer goods packaging is accelerating although slowly, according to a report produced by the UK-based Green Alliance Circular Economy Task Force (CETF) comprising of members including Kingfisher, Viridor, Walgreens Boots Alliance, SUEZ recycling and recovery UK, and Veolia.